I’m thrilled to sit down with Dominic Jainy, an IT professional whose deep expertise in artificial intelligence, machine learning, and blockchain brings a unique perspective to the intersection of technology and sustainable energy solutions. Today, we’re diving into the Democratic Republic of Congo’s ambitious vision for the Inga hydroelectric site, a potential powerhouse that could transform the region by fueling energy-intensive industries like AI data centers. Our conversation explores the site’s incredible potential, the challenges of unlocking its capacity, and how it could become a game-changer for tech giants seeking green power.

Can you tell us what sets the Inga site on the Congo River apart from other hydroelectric projects globally?

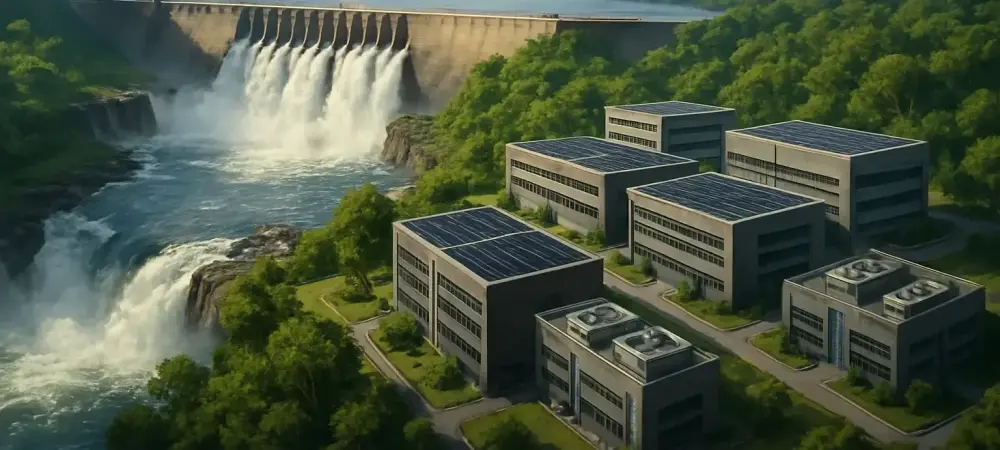

Absolutely, the Inga site is truly one of a kind. Its potential capacity of 44 gigawatts is staggering—nearly double that of China’s Three Gorges Dam, which is often seen as the benchmark for massive hydro projects. What makes Inga stand out is not just the raw power potential but also the natural advantages it offers. The Congo River provides an immense, consistent flow of water, which is ideal for sustained energy generation and even cooling systems for energy-hungry facilities like data centers. It’s a rare combination of scale and strategic benefits that you don’t see in many other locations.

What do you see as the biggest roadblocks to fully developing Inga’s capacity, given it currently produces less than 2 gigawatts?

The challenges are multifaceted, and they’ve been persistent for decades. Logistically, the region faces significant hurdles—building infrastructure in such a remote and complex environment is no small feat. Financially, the costs are enormous; we’re talking billions of dollars for projects like Inga III or the broader Grand Inga vision of eight dams. Past attempts have been stalled by funding gaps and governance issues, which have delayed timelines significantly. It’s a classic case of immense potential being held back by practical constraints that require both local and international cooperation to overcome.

Why do you think the Inga site is such a strong candidate for powering AI data centers specifically?

AI data centers are incredibly power-hungry. Training advanced models and maintaining the infrastructure for artificial intelligence requires gigawatts of electricity—sometimes enough to power hundreds of thousands of homes. Inga’s potential to deliver cheap, green energy at that scale is a perfect match. On top of that, the site’s proximity to fiber connections means data can move quickly and efficiently, which is critical for tech companies. It’s not just about power; it’s about creating an ecosystem where energy and connectivity align to meet the demands of cutting-edge technology.

How does the government’s strategy of partnering with data centers fit into the broader plan for Inga’s development?

The government sees data centers as ideal partners because they can provide a steady, high-demand customer base to justify the massive investment needed to expand Inga. The idea is to create a symbiotic relationship where tech companies get access to sustainable power at a competitive cost, while the revenue and investment help scale up the hydro site. Balancing this with other local needs, like powering the copper mining industry, is tricky but essential. It’s about prioritizing projects that drive economic growth while ensuring the benefits are spread across different sectors.

With the World Bank committing $1 billion to the project, how do you think this funding will impact Inga’s progress?

This funding is a game-changer. The initial $250 million expected this year will likely go toward critical preparatory work—feasibility studies, environmental assessments, and early infrastructure planning. Beyond the dollars, the World Bank’s involvement signals credibility to private investors. Through mechanisms like the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency, they’re helping to de-risk the project, making it more attractive for the private sector to jump in. It’s a catalyst that could finally get the ball rolling after years of delays.

The estimated cost for Inga III is around $2 million per installed megawatt. Can you break down what contributes to that figure?

That $2 million per megawatt covers a wide range of expenses. A significant chunk goes to the core infrastructure—building the dam itself, turbines, and related systems. But a big portion also includes transmission lines, which are crucial because the power needs to reach where it’s needed, whether that’s local industries or data centers. You’ve also got costs for planning, regulatory compliance, and mitigating environmental impacts. For a project like Inga III, estimated at over $20 billion for 11 gigawatts, every aspect of development adds up quickly.

Looking ahead, what’s your forecast for the role of hydroelectric projects like Inga in meeting the energy demands of emerging technologies?

I’m optimistic but realistic. Projects like Inga have the potential to be cornerstones in powering the future of technology, especially for energy-intensive fields like AI and blockchain. The push for sustainable, green energy aligns perfectly with hydro’s strengths, and as tech companies face increasing pressure to reduce their carbon footprint, sites like Inga could become strategic hubs. However, the key will be execution—overcoming the logistical and financial barriers to bring this potential to life. If done right, I see Inga not just as a power source, but as a model for how renewable energy can drive innovation on a global scale.