Navigating the high-stakes environment of a data modeling interview requires much more than a simple recitation of technical definitions; it demands a demonstrated ability to think strategically about how data structures serve business objectives. The most sought-after candidates are those who can eloquently articulate the trade-offs inherent in every design decision, moving beyond the “what” to explain the critical “why.” An interviewer’s goal is to unearth a professional who can seamlessly translate complex business requirements into logical, efficient, and scalable data models. Success, therefore, is not measured by the quantity of knowledge but by the quality of its application—the ability to discuss foundational principles, compare architectural patterns, and address real-world challenges with nuance and foresight. The path to acing the interview is paved with a deep, contextual understanding that showcases not just a technician, but a true data architect.

The Foundation: Mastering the Core Concepts

The Three Layers of a Data Model

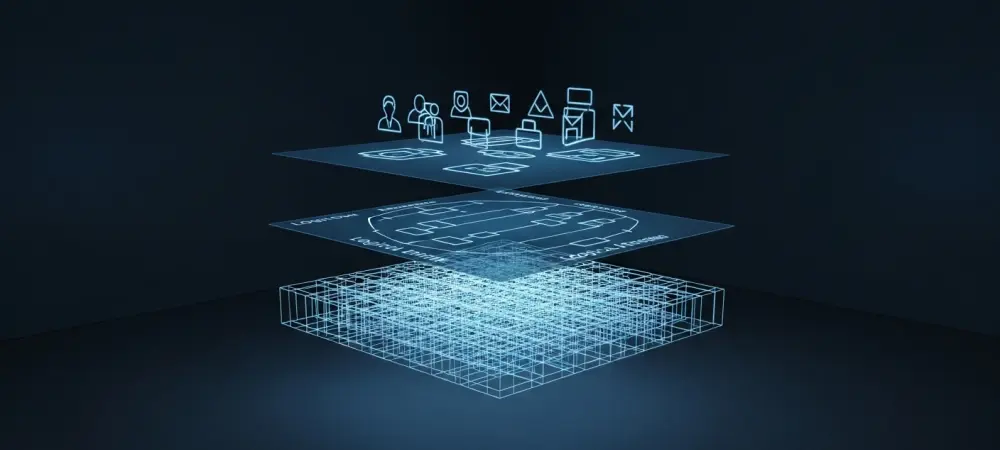

A comprehensive understanding of the distinct layers of data modeling is non-negotiable, as each serves a unique audience and purpose within an organization. The journey begins with the Conceptual Data Model, which operates at the highest level of abstraction. This model is intentionally devoid of technical jargon and focuses purely on identifying the core business entities—such as “Customer,” “Product,” and “Order”—and the fundamental relationships that connect them. Its primary function is to facilitate communication and validation with business stakeholders, ensuring that the proposed data structure accurately reflects the operational realities and strategic goals of the enterprise. By presenting a simplified, high-level view, the conceptual model guarantees alignment between the technical team and the business users before any significant development resources are committed, acting as a foundational agreement on the scope and nature of the data to be managed. A candidate must articulate its role as a strategic tool for business alignment, not merely a preliminary sketch.

From this high-level agreement, the process descends into greater detail with the Logical Data Model and, subsequently, the Physical Data Model. The logical model serves as an intermediary blueprint, enriching the conceptual view with specific attributes for each entity and defining the relationships with more precision through primary and foreign keys. Crucially, it remains independent of any particular database management system (DBMS), allowing architects to design the data’s structure without being constrained by the technical limitations of a specific technology. This technology-agnostic nature makes it a vital document for system designers and analysts. Finally, the physical model translates this logical structure into a concrete, implementation-ready schema for a chosen DBMS. It defines exact table names, column data types (e.g., VARCHAR, INT, DATETIME), indexes, and other database-specific constraints. Demonstrating a clear understanding of this progression—from the business-focused conceptual to the technology-agnostic logical to the implementation-specific physical—showcases a mature grasp of the entire data modeling lifecycle.

The Essential Building Blocks

The entire discipline of data modeling is built upon a few fundamental components that form its universal language. At the core are entities and attributes. An entity represents a distinct, real-world object or concept about which an organization needs to store information. For example, in a university system, entities would include “Student,” “Professor,” and “Course.” These conceptual entities are ultimately manifested as tables within a database. Each entity possesses attributes, which are the specific properties or characteristics that describe it. For the “Student” entity, attributes might include “StudentID,” “FirstName,” “LastName,” and “Major.” These attributes become the columns or fields within the corresponding database table. The ability to correctly identify relevant entities and their essential attributes from a business requirement is a primary skill that interviewers test, as it forms the bedrock of any successful database design. Without a solid grasp of these basics, no model can accurately represent the business domain.

Communicating the structure derived from these building blocks is equally important, and the primary tool for this is the Entity Relationship Diagram (ERD). An ERD is a graphical representation that visually illustrates the logical structure of a database, showing the entities as boxes and the relationships between them as lines. It is the definitive blueprint that allows stakeholders, from business analysts to database administrators, to understand and validate the model’s design at a glance. A candidate should be able to not only interpret an ERD but also discuss its role in the design process. It is a powerful communication device that clarifies complex relationships, identifies potential issues early on, and serves as living documentation for the database. Proficiency with ERDs signifies an ability to translate abstract requirements into a tangible and communicable design, a skill that is indispensable for collaborative development and long-term system maintenance.

The Art of Structure: Normalization and Relationships

The Balancing Act: Normalization vs Denormalization

One of the most nuanced and critical discussions in data modeling revolves around the strategic push and pull between normalization and denormalization. Normalization is a systematic process for organizing the columns and tables in a relational database to minimize data redundancy and improve data integrity. The primary goals are to eliminate useless or repeated data, thereby saving storage space and preventing update anomalies where changing a piece of data in one place might leave it unchanged in another. By breaking down large tables into smaller, well-structured tables and defining clear relationships between them, normalization reduces overall data complexity and ensures that data dependencies are logical and coherent. A candidate is expected to understand that this process is not merely an academic exercise; it is a crucial technique for building robust, maintainable, and scalable transactional systems where data consistency is paramount. The ability to explain how normalization safeguards data integrity is a hallmark of a disciplined data modeler.

In direct opposition stands denormalization, the intentional process of introducing redundancy into a database design to optimize read performance. While normalization is ideal for write-heavy online transaction processing (OLTP) systems, it can lead to slow query performance in read-heavy online analytical processing (OLAP) or reporting systems, as retrieving data often requires complex joins across many tables. Denormalization counters this by strategically combining tables or adding redundant data columns, thereby reducing the number of joins needed for frequent queries. This is not a design flaw but a calculated trade-off: sacrificing some storage efficiency and write performance to gain significant speed in data retrieval. A top-tier candidate will frame this not as a simple choice but as a strategic decision based on the application’s specific needs. They must be able to articulate when denormalization is appropriate, such as in a data warehouse environment, and discuss the associated risks, like the increased complexity of keeping redundant data synchronized.

Forging Connections: Keys and Relationships

The integrity and functionality of a relational database depend entirely on how its tables are interconnected, a task managed through keys and relationships. Interviewers will probe a candidate’s understanding of different key types, with a particular focus on the distinction between a natural key and a Surrogate Key. A natural key is an attribute that is already present in the data and uniquely identifies a record, such as a Social Security Number or an email address. A surrogate key, by contrast, is an artificially generated identifier—typically an integer—with no intrinsic business meaning. While natural keys seem intuitive, they can be problematic if they change over time or are not guaranteed to be unique. Surrogate keys provide a stable, immutable, and simple way to uniquely identify records, simplifying query joins and often improving performance. A strong candidate can weigh the pros and cons of each, explaining why surrogate keys are often the preferred choice in modern database design for ensuring stability and decoupling the database’s internal logic from external business identifiers.

Beyond keys, a deep understanding of relationship types is essential for accurately modeling the business domain. An ERD visually represents these connections, and a candidate must be able to explain the different semantics. A key distinction is between an identifying relationship and a non-identifying relationship. In an identifying relationship, the primary key of the parent entity is included as part of the primary key of the child entity, signifying a strong dependency where the child cannot exist without the parent. This is often depicted with a solid line. A non-identifying relationship is weaker; the parent’s primary key is included in the child table as a foreign key but not as part of its primary key. Furthermore, demonstrating knowledge of more complex patterns, like a self-recursive relationship where a table has a foreign key that references its own primary key (e.g., an “Employee” table where a manager is also an employee), shows a capacity to handle sophisticated, real-world modeling challenges.

Designing for Insight: Data Warehousing Principles

Schemas for Analytics: Star vs Snowflake

When the focus shifts from transactional databases to data warehousing for business intelligence and analytics, the design philosophy changes, and schema patterns become a central topic of discussion. The most prevalent and fundamental of these is the Star Schema. This design is characterized by its simplicity, featuring a central Fact Table surrounded by several Dimension Tables. The fact table contains quantitative business metrics or “facts” (e.g., SalesAmount, QuantitySold), while the dimension tables hold descriptive attributes that provide context to the facts (e.g., Time, Product, Customer). Its structure, resembling a star, is highly denormalized, which minimizes the number of joins required for queries. This makes it extremely efficient for the slicing and dicing operations common in data analysis and reporting. A candidate must clearly explain that the star schema’s primary advantages are its straightforwardness, which makes it easy for analysts to understand, and its superior query performance for most analytical workloads.

As an evolution of the star schema, the Snowflake Schema introduces a higher degree of normalization. In this model, the dimension tables are themselves normalized into multiple related tables. For example, a “Product” dimension might be broken down into “Product,” “ProductCategory,” and “ProductSubcategory” tables. The resulting ERD resembles a snowflake, with branches extending from the central fact table. The main advantage of this approach is the reduction of data redundancy within the dimensions, which can save storage space and simplify data maintenance. However, this comes at a significant cost: queries become more complex, requiring more joins to retrieve the necessary contextual information, which can negatively impact performance. An adept candidate will articulate this trade-off clearly, positioning the snowflake schema as a valid choice when dimension tables are very large and data integrity within the dimensions is a high priority, but acknowledging that the star schema is generally preferred for its performance and simplicity.

Managing Data Over Time and Detail

A critical function of a data warehouse is to provide a historical perspective on business operations, which requires careful management of data detail and changes over time. The concept of granularity is fundamental to this, referring to the level of detail or depth of the information stored in a fact table. A table with high granularity contains transaction-level data (e.g., individual sales records), enabling highly detailed analysis. Conversely, low granularity implies that the data is summarized or aggregated (e.g., daily sales totals). The choice of granularity is a critical design decision that directly impacts storage requirements and the types of questions that can be answered by the data. Alongside this, the management of historical data is often handled through Slowly Changing Dimensions (SCDs). These are techniques used to track and manage changes in dimension attributes over time. A candidate should be able to discuss different SCD types, explaining how they allow an organization to report on data as it was at a specific point in the past, a capability essential for accurate historical analysis.

To further refine data warehouse design and improve usability, modelers employ specialized dimensions to handle specific scenarios. One such technique is the Junk Dimension, a practical solution for dealing with a collection of low-cardinality flags or indicators that often clutter a fact table. Instead of having numerous small, unrelated columns in the fact table (e.g., “IsOnSale,” “HasCoupon,” “PaymentType”), these attributes are consolidated into a single, more manageable dimension table. This cleans up the fact table, reduces its size, and organizes disparate attributes into a coherent structure. Another important concept is the Confirmed Dimension, which is a dimension that is shared across multiple fact tables, often managed by a central team. Using confirmed dimensions for entities like “Customer” or “Date” ensures that different business processes use a consistent, integrated view of the data, enabling cross-functional analysis and creating a “single source of truth” across the entire data warehouse. Discussing these practical techniques demonstrates an understanding of the real-world challenges of building a scalable and maintainable analytics platform.

Real-World Scenarios and Modern Challenges

Avoiding Common Pitfalls and Engineering the Solution

An interview will almost certainly probe a candidate’s practical experience by asking about common mistakes and challenges encountered in data modeling. Being able to identify these pitfalls demonstrates a level of maturity that comes from real-world application. One frequent error is creating overly broad models with an excessive number of tables, which can become unmanageably complex and difficult to maintain. Another is the unnecessary use of surrogate keys when a stable and perfectly suitable natural key already exists. Perhaps the most critical mistake is designing a model with a lack of clear business purpose, which inevitably results in a solution that fails to meet user needs. A strong response involves not just listing these errors but also explaining their consequences and how to proactively avoid them through clear communication with stakeholders and a disciplined design process. It shows an awareness that data modeling is as much about project management and business analysis as it is about technical implementation.

Beyond avoiding errors, a proficient data modeler must be adept at using tools to bring designs to life and to understand existing systems. This is where the concepts of forward and reverse engineering come into play. Forward engineering is the process of generating the Data Definition Language (DDL) scripts from a completed data model to automatically create the database schema, including tables, keys, and constraints. This automates the transition from design to implementation, ensuring accuracy and consistency. Conversely, reverse engineering is the process of creating a data model by analyzing an existing database schema or its DDL scripts. This is an invaluable skill when tasked with documenting, modifying, or migrating a legacy system where the original design documentation is missing or outdated. Demonstrating fluency with both processes indicates a versatile skill set, showing that the candidate can not only create new systems from scratch but also effectively work with and improve existing ones.

Adapting to the Modern Data Landscape

A seasoned professional understands that theoretical rules must often bend to accommodate practical realities. A classic example is the debate over strict adherence to Third Normal Form (3NF). While 3NF is a critical benchmark for achieving a high degree of normalization in transactional systems, the assertion that all databases must conform to it is a fallacy. In many contexts, particularly in reporting and analytical systems, denormalized databases offer significant advantages. They can be more accessible to end-users, easier to query, and, most importantly, can deliver vastly superior performance for complex data retrieval operations. A top-tier candidate will confidently argue that the choice of normalization level is a strategic decision, not a rigid rule. It requires a thoughtful analysis of the system’s specific read/write patterns, performance requirements, and data integrity needs, demonstrating a pragmatic and results-oriented approach to database design.

Finally, a forward-looking data modeler must recognize that the data landscape extends far beyond traditional relational databases. The rise of NoSQL databases has introduced a new paradigm for data storage and management, and a candidate must be able to discuss its role in the modern data ecosystem. NoSQL databases offer several key advantages over their relational counterparts, including the ability to store unstructured or semi-structured data without a predefined schema, which provides immense flexibility. They are designed for horizontal scalability through a process called sharding, allowing them to handle massive volumes of data and high traffic loads. Additionally, their distributed nature often provides enhanced fault tolerance through data replication. A candidate who had successfully demonstrated an ability to articulate these benefits would have shown not only a mastery of traditional modeling principles but also an awareness of when and why to employ different architectural patterns, positioning them as a versatile expert ready to tackle the diverse challenges of today’s data-driven world.