The gap between machine perception and biological sight has long been a defining challenge in robotics, with conventional systems struggling to match the instantaneous reflexes of living organisms. The neuromorphic vision chip represents a significant advancement in real-time robotic perception, aiming to close this gap. This review will explore the evolution of this brain-inspired technology, its key features, performance metrics, and the impact it has had on various applications. The purpose of this review is to provide a thorough understanding of the technology, its current capabilities, and its potential future development.

An Introduction to Neuromorphic Vision

Neuromorphic vision technology represents a paradigm shift in how machines see, drawing its core principles directly from the architecture of the human brain. Unlike traditional cameras that capture and process a series of complete images, or frames, neuromorphic systems operate on a fundamentally different principle. They are designed to perceive the world dynamically, focusing only on changes within a scene, much like biological vision prioritizes motion and new stimuli.

This approach emerged as a direct response to the inherent latency and computational inefficiency of frame-based vision systems. Processing sequential, data-heavy frames consumes significant power and introduces delays, which can be detrimental in high-stakes applications like autonomous driving or surgical robotics. By creating a system that is inherently event-driven, neuromorphic technology provides a pathway toward more responsive, efficient, and ultimately safer autonomous machines capable of reacting to their environment in real time.

Core Architecture and Operating Principles

Replicating the Lateral Geniculate Nucleus LGN

At the heart of this innovation is a custom-designed chip that emulates the function of a crucial but often overlooked part of the brain: the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN). In the human visual pathway, the LGN serves as an intelligent relay station between the retina and the visual cortex. It does not simply pass along information; it actively filters and prioritizes visual data, allowing the brain to allocate its formidable processing power to areas where change or motion is detected.

The research team successfully translated this biological function into silicon, creating a “selective attention” mechanism for machines. The chip acts as a filter, preemptively identifying the most important parts of a visual scene based on movement. This allows the system to focus its computational efforts where they are needed most, rather than wasting resources analyzing static, unchanging backgrounds. This mimicry of a natural, efficient biological process is a central tenet of the technology’s design.

Event-Based vs Frame-Based Sensing

The operational distinction between this neuromorphic approach and conventional machine vision lies in the shift from frame-based to event-based sensing. Traditional cameras capture the entire visual field at fixed intervals, generating a sequence of frames. Each frame contains a massive amount of redundant information, as most of a scene typically remains static from one moment to the next. The system must then use computationally expensive algorithms, like optical flow, to compare these frames and deduce motion.

In contrast, the event-based sensor works by monitoring individual pixels for changes in light intensity over time. A pixel only transmits data—an “event”—when it detects a significant change. This asynchronous process effectively bypasses the analysis of static visual data entirely. As a result, the system’s output is not a series of images but a sparse stream of events corresponding only to the dynamic elements within the scene. This method dramatically reduces data volume and focuses computational resources exclusively on what is moving, enabling near-instantaneous perception.

Performance Breakthroughs and Key Innovations

The practical benefits of this brain-inspired architecture have been demonstrated through rigorous testing, revealing substantial performance gains over established methods. In simulated tasks designed to mimic real-world scenarios, such as autonomous driving and the operation of robotic arms, the neuromorphic prototype showcased its superior responsiveness. The system achieved a remarkable 75% reduction in processing delays, a critical factor for any machine that needs to react swiftly in a dynamic environment.

Moreover, the chip’s ability to focus on motion-centric data resulted in a twofold increase in motion-tracking precision. By filtering out irrelevant background information and concentrating processing power on moving objects, the system can follow targets with greater accuracy than conventional methods that are often bogged down by analyzing entire frames. These quantitative advancements set a new performance benchmark, illustrating the tangible advantages of adopting a more biologically plausible approach to machine vision.

Applications in Robotics and Autonomous Systems

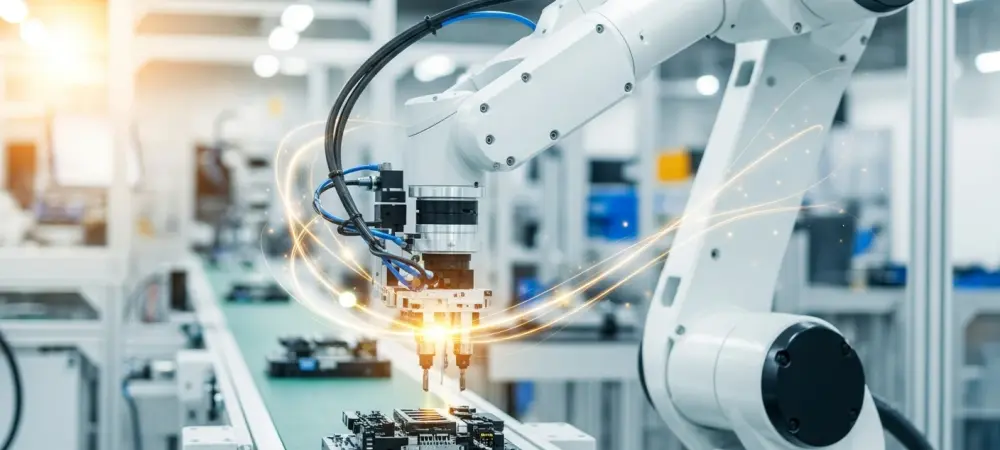

The real-world implications of this technology are far-reaching, with significant potential to enhance safety and efficiency across multiple industries. In the realm of autonomous vehicles, the ability to slash processing delays could mean the difference between a timely stop and a collision. Similarly, industrial robots on a fast-moving assembly line could operate with greater precision and safety around human workers, thanks to enhanced reflexes.

Beyond these established fields, the technology opens doors to more sophisticated and nuanced applications. In surgical automation, robots could respond instantly to subtle movements, improving procedural accuracy. It also promises to enable more natural and intuitive human-robot interactions. A machine equipped with this vision system could interpret subtle gestures and body language in real time, paving the way for seamless collaboration in manufacturing, healthcare, and even domestic settings.

Current Challenges and Technical Limitations

Despite its impressive performance, the neuromorphic vision chip is not without its hurdles. One of the primary technical limitations is its continued reliance on standard optical-flow algorithms for the final stage of image interpretation. While the chip excels at identifying where motion is occurring, it still hands off that filtered data to conventional software for detailed analysis, creating a potential bottleneck. The system can also struggle in visually cluttered or “crowded” environments, where an overwhelming number of simultaneous events might challenge its filtering capabilities. Furthermore, a significant development challenge lies ahead in scaling the hardware for widespread adoption. Moving from a successful prototype to a commercially viable product that can be integrated seamlessly into existing robotics and AI frameworks requires considerable engineering effort. Overcoming these obstacles will be crucial for the technology to transition from a promising research concept to a foundational component of next-generation autonomous systems.

The Future of Machine Perception

The trajectory of this technology points toward a future where machines perceive the world less like cameras and more like biological organisms. Future development will likely focus on two key areas: enhancing hardware scalability to make the chips more accessible and powerful, and achieving deeper, more native integration with advanced artificial intelligence. This could involve developing novel AI models designed specifically to work with the sparse, event-based data that neuromorphic sensors produce.

In the long term, the impact of this work could be transformative, fundamentally redefining the relationship between machines and a world in constant motion. As this technology matures, it could grant autonomous systems the kind of effortless, instantaneous environmental awareness that humans take for granted. This would not only make them safer and more efficient but also more capable of complex, interactive tasks, heralding a new era of machine perception.

Conclusion

The neuromorphic vision chip stands as a compelling example of how principles from neuroscience can directly address longstanding engineering challenges. Its brain-inspired architecture, centered on a silicon-based LGN, offers a clever and effective solution to the latency issues that plague traditional vision systems. The resulting performance gains—faster processing and more precise motion tracking—are not merely incremental improvements but significant leaps forward. While challenges related to software integration and hardware scaling remain, the technology’s potential to drive advancements in safety and efficiency across the robotics and autonomous systems sectors is undeniable. It represents a critical step toward creating machines that can perceive and react to the world with biological-level grace and speed.