Today, we’re diving deep into the rapidly evolving ransomware landscape with an expert who has spent years dissecting the tools, tactics, and procedures of cybercriminal groups. We’ll be discussing the emergence of a new, unusually mature ransomware-as-a-service operation known as “Vect.” Our conversation will explore the group’s custom-built malware, its sophisticated operational security measures designed to ensure anonymity, and the specific attack techniques it uses to bypass modern defenses. We will also touch on what its recruitment strategies and multi-platform targeting reveal about its ambitions and what organizations can do to protect themselves.

New ransomware groups often repurpose leaked code. Vect, however, claims to use custom C++ malware with ChaCha20 encryption. What specific advantages does this give them over groups using code from Lockbit or Conti, and how does it complicate traditional detection efforts for security teams?

It’s a massive advantage that immediately elevates them from the typical “script kiddie” level. When groups reuse leaked source code from giants like Conti or Lockbit, they’re also inheriting their digital fingerprints. Security tools, threat hunters, and researchers have spent years building detections for those specific codebases. By developing their malware from scratch in C++, Vect creates a clean slate. This custom approach means they aren’t bogged down by the known weaknesses or detectable patterns of their predecessors, making signature-based antivirus almost completely blind to their initial payload. The choice of the ChaCha20-Poly1305 algorithm is also a deliberate, tactical decision. It’s not just about strong encryption; it’s about speed. On systems without specialized hardware acceleration for AES, it can be two-and-a-half-times faster. For a security team, that’s a nightmare scenario—the time from initial execution to widespread encryption is drastically reduced, leaving them with almost no window to react before critical systems are locked down.

Threat actors are increasingly focused on operational security. Considering the use of Monero for payments, the TOX protocol for communications, and a TOR-only infrastructure, could you break down how this combination creates such a high degree of anonymity for the Vect group?

This triad of technologies creates a formidable fortress of anonymity that signals we’re dealing with seasoned professionals. Each piece is chosen to sever a different link that investigators would typically follow. Using Monero for payments, instead of a more transparent cryptocurrency, makes tracing the money flow incredibly difficult for law enforcement. The TOX protocol for affiliate communication is another shrewd move; it’s a peer-to-peer, encrypted messaging system that doesn’t rely on central servers that could be seized or monitored. This keeps their internal chatter and planning completely off the grid. Finally, running their entire infrastructure—leak sites, command-and-control servers—exclusively as TOR hidden services means there’s no clearnet presence to analyze or attack. When you put it all together, you have a ghost operation: the financial trail is obscured, the communications are decentralized and encrypted, and the infrastructure is buried within the dark web. It’s a clear indication that these aren’t amateurs; they’ve learned from the mistakes of other groups and built their operation for long-term survival.

The group reportedly employs intermittent encryption for speed and Safe Mode execution to evade security tools. Can you walk us through how these two tactics work in tandem during an attack and what specific early warning signs a security operations center might otherwise miss?

These two tactics are a devastating one-two punch designed to be both fast and stealthy. First, the malware forces the infected machine to reboot into Safe Mode. This is a brilliant evasion technique because Safe Mode loads only the most essential drivers and services, meaning most endpoint security tools—antivirus, EDR agents—are disabled and won’t even be running. It’s like a thief disabling the alarm system before they start ransacking the house. Once in this unprotected state, the ransomware begins its work, but it doesn’t encrypt entire files. Instead, it uses intermittent encryption, scrambling only small blocks of data within each file. This is purely a play for speed. Why waste time encrypting a whole 10-gigabyte database file when you can make it completely unusable by encrypting just a few megabytes? For a SOC, the warning signs are incredibly subtle and easily missed. A suspicious reboot into Safe Mode might be flagged, but it could be mistaken for a legitimate system maintenance task. Because the encryption is so rapid and selective, the typical high-I/O alerts that full encryption would trigger might not fire. By the time the SOC realizes what’s happening, the damage is already done across multiple systems.

This group is actively targeting Windows, Linux, and VMware ESXi systems while reportedly recruiting affiliates with waived fees for CIS members. What does this multi-platform approach indicate about their ambitions, and how does their recruitment strategy influence their choice of future targets?

Targeting Windows, Linux, and especially VMware ESXi right out of the gate is a huge statement of intent. It shows they aren’t just going after low-hanging fruit like individual workstations. They are aiming squarely at the heart of the modern enterprise: the virtualized infrastructure. Encrypting an ESXi hypervisor can take dozens or even hundreds of virtual servers offline in a single stroke, causing maximum disruption and giving them immense leverage in ransom negotiations. This signals a level of ambition to compete with the top-tier RaaS groups. Their recruitment strategy is equally telling. By waiving the $250 entry fee for affiliates from the Commonwealth of Independent States, they are not only hinting at their own likely geographic origin but also actively courting experienced, Russian-speaking partners. These are often the most skilled and aggressive affiliates in the ecosystem. This will absolutely influence their target selection, steering them towards larger, more lucrative organizations in Western countries that these experienced affiliates are adept at compromising.

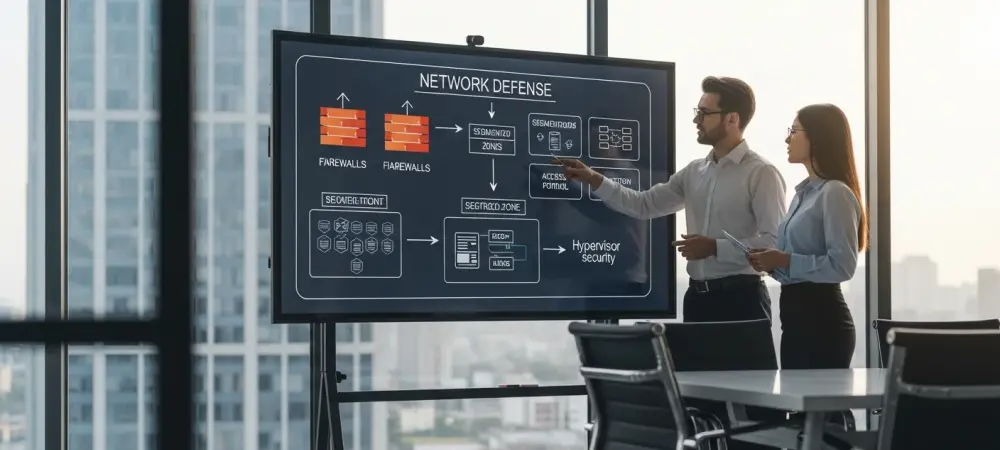

Given that Vect may seek compromised Fortinet accounts for initial access, what are the most critical, practical steps an organization should take to harden its edge appliances and segment its hypervisor management planes?

This is where the basics become absolutely non-negotiable. First and foremost, harden those edge appliances like Fortinet devices. This means immediately applying security patches—don’t wait for the next maintenance window. You have to restrict administrative access to these interfaces; they should never be exposed directly to the public internet. Enforce multi-factor authentication for every single remote and privileged account without exception. This alone can stop an attack using stolen credentials in its tracks. For the hypervisor environment, segmentation is key. The VMware management plane should be on its own isolated network, completely separate from user traffic and general server networks. Access to it should be strictly controlled through jump boxes or bastion hosts, with rigorous logging and monitoring. Limit any lateral movement paths by tightening firewall rules and restricting the use of administrative protocols like RDP or SSH between different network segments. The goal is to create a series of locked doors, so even if they breach the perimeter, they can’t easily move to seize the crown jewels—your virtual infrastructure.

What is your forecast for the ransomware-as-a-service landscape?

I believe we are entering a new phase of hyper-specialization and operational maturity. The days of unsophisticated, noisy ransomware are fading. The future belongs to groups like Vect that operate like lean, efficient tech startups. We’ll see more custom-built, multi-platform malware that is faster and more evasive than ever before. The RaaS model will continue to professionalize, with groups offering slick affiliate portals, 24/7 support, and sophisticated operational security that makes attribution and takedowns exceedingly difficult. I also predict that the focus on attacking core infrastructure, particularly hypervisors and cloud environments, will intensify. It’s the path of least resistance to maximum impact, and these groups are all about maximizing their leverage. The barrier to entry may get slightly higher, but the rewards for the successful, mature groups will be greater, leading to a more dangerous and resilient threat landscape.