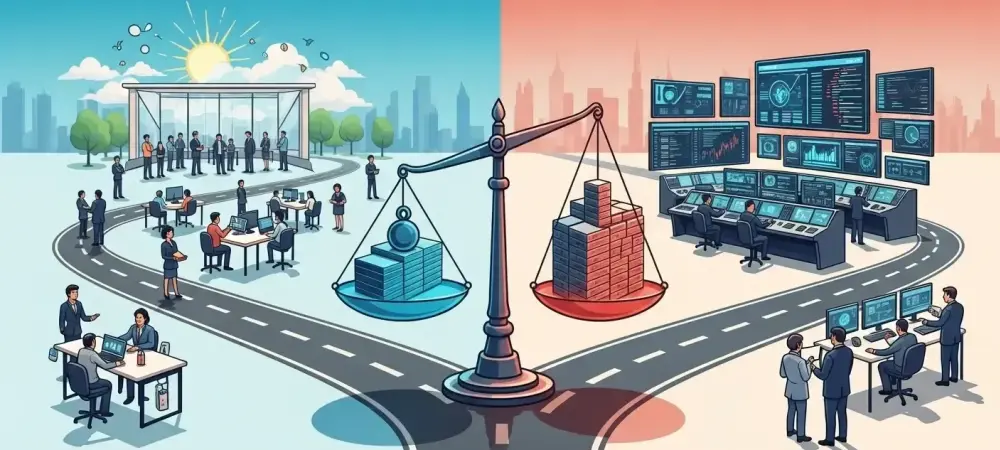

In the complex and rapidly evolving landscape of software development, organizations are perpetually navigating a critical crossroads that defines their entire operational and cultural identity. The fundamental tension between granting engineering teams full autonomy and enforcing centralized control has become the central strategic challenge in scaling modern DevOps practices. This is not a simple technical debate but a profound choice that directly influences developer velocity, company culture, the integrity of security measures, and the ability to respond to ever-changing market demands. One path champions the creative freedom of the individual developer, believing innovation thrives in an environment of trust and ownership, while the opposing path prioritizes business alignment, consistency, and efficiency through carefully constructed, centralized platforms. How leaders resolve this conflict ultimately dictates whether their organization is optimized for unleashed experimentation or streamlined, predictable execution.

The Path of Empowerment and Its Inherent Risks

The Developer Empowerment model is rooted in a philosophy of profound trust, operating on the principle that experienced engineers deliver their best work when afforded the freedom to select their tools and govern their own processes. Organizations adopting this approach intentionally move away from rigid, top-down mandates, instead providing guidance through curated tool catalogs, internal documentation, and approved vendor lists. This empowers individual teams to tailor their workflows, experiment with emerging technologies, and assume complete ownership of their software development lifecycle. According to a comprehensive 2025 survey of over 10,000 professional developers, this empowered group constitutes a significant portion of the industry, representing 34% of respondents. The primary advantage of this model is its direct impact on developer satisfaction and retention; engineers feel valued and engaged, which is a critical factor in a competitive talent market. Furthermore, this decentralization allows for agile responses to newly discovered security threats, as teams can act immediately without the bureaucratic delays of a central platform team.

However, this level of autonomy introduces a distinct set of challenges and security implications that cannot be ignored. While the model fosters a deeper technical expertise among developers, it simultaneously risks creating a fragmented and inconsistent security posture across the organization. The same survey data revealed that empowered teams demonstrate higher adoption rates of developer-centric security tools, with 32% integrating IDE security checks, 28% using container scanning, and 20% employing pre-commit hooks. The downside is that successful security configurations or threat mitigations developed by one team may remain siloed, preventing the rest of the organization from benefiting from that knowledge. Different teams may adhere to varying levels of diligence, creating potential blind spots and compliance gaps. This freedom becomes a particularly acute liability when extended to developers who lack a strong background in security, as they may inadvertently introduce significant vulnerabilities, turning a strategy meant to foster innovation into a source of organizational risk.

The Pursuit of Efficiency Through Centralization

In direct opposition to the empowerment model, the Business-Focused approach seeks to maximize developer productivity by abstracting away the underlying complexities of infrastructure, security, and deployment. This is most often realized through the implementation of a centralized Internal Developer Platform (IDP) or a strictly controlled set of pre-configured tools. The core objective is to shield developers from the cognitive overhead of managing toolchains, allowing them to focus entirely on writing code that directly addresses business needs and delivers product value. Within this paradigm, developers interact with simplified interfaces; for example, they might execute a single command to deploy an application without needing to know whether the underlying infrastructure is Kubernetes, ECS, or Cloud Run. This approach is particularly prevalent in large enterprises and highly regulated industries where the potential chaos of thousands of disparate toolchains would create an unmanageable maintenance and security burden. It prioritizes consistency, compliance, and operational stability above all else. This centralized model excels at enforcing uniform security and operational standards, which is indispensable for meeting stringent compliance requirements and simplifying audits. The data reflects its effectiveness in implementing “behind-the-scenes” security measures; developers in this group, making up 27% of those surveyed, reported higher adoption rates of Software Composition Analysis (SCA) at 29%, Dynamic Application Security Testing (DAST) at 26%, and Interactive Application Security Testing (IAST) at 27%. Yet, this efficiency comes with significant drawbacks. The high level of abstraction can create a “black box” effect, preventing developers from understanding underlying systems, which complicates debugging and fosters a shallower grasp of security principles. Moreover, the central platform team can easily become a bottleneck, as all requests for new tools or features must pass through them, slowing down innovation. If the platform is too rigid or slow to adapt, frustrated developers may resort to unauthorized “shadow IT,” thereby undermining the very consistency the model was designed to protect.

Navigating a Strategic Decision Beyond a False Dichotomy

Ultimately, the intense industry debate between developer autonomy and centralized control represented a false choice. The success of a DevOps strategy was never determined by the structural decision alone, but rather by how effectively that structure supported the organization’s unique context, processes, and culture. The most forward-thinking organizations understood that instead of asking which approach was universally superior, they needed to ask what their specific circumstances demanded. This required a nuanced evaluation of several critical factors. An organization’s size and growth trajectory were paramount; a model that fostered innovation in a small startup inevitably failed to provide the necessary stability for a large enterprise. Similarly, the security maturity of the engineering teams played a crucial role, as senior, security-savvy teams were often stifled by the guardrails that were essential for less experienced teams. This strategic choice was not a permanent declaration but an evolutionary process, with organizations intelligently shifting along the spectrum as their needs changed.