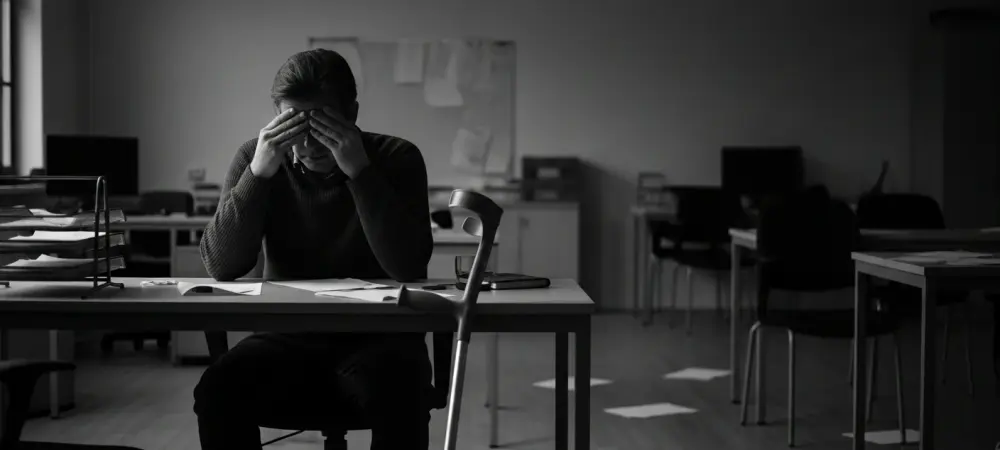

A highly skilled professional can deliver a stellar presentation one day and require a cane to navigate the office the next, yet it is often the appearance of the cane that reshapes how their unchanging expertise is perceived by colleagues and leadership. This disconnect between a person’s consistent talent and their fluctuating physical reality creates a silent but immense pressure for countless employees with dynamic or invisible disabilities. In workplaces built on the assumption of physical uniformity, the need to conceal one’s reality becomes a survival strategy, fostering a culture of fear that ultimately costs both the individual and the organization. This phenomenon reveals a deep-seated flaw in modern corporate structures, forcing a critical examination of what it truly means to be a productive and valued member of a team.

When Expertise Is Constant but Mobility Is Not

A fundamental misunderstanding fuels the need for concealment: the belief that for a disability to be legitimate, it must be permanent, visible, and unwavering. This narrow definition fails to encompass the reality of chronic illnesses, autoimmune disorders, and pain conditions, where symptoms can vary dramatically day by day. An employee’s intellectual capacity and professional commitment do not diminish on days they experience pain or fatigue, yet the corporate world often struggles to reconcile this. The environment is frequently designed around an outdated “ideal worker” who is perpetually healthy and physically consistent.

This issue becomes particularly acute for ambulatory mobility aid users, whose need for a cane, crutches, or a wheelchair can fluctuate. The sudden appearance of such a device can trigger a shift in perception among managers and peers. Questions about reliability, capability, and long-term potential may arise, not based on performance, but on a visual cue that deviates from the norm. Consequently, the employee is placed in a difficult position, forced to manage not only their health but also the inconsistent and often biased reactions of their professional circle.

The Myth of the Ideal Worker and Challenging Corporate Norms

Deeply ingrained in many corporate cultures is the archetype of the ideal employee: someone who is always physically present, travels without issue, and demonstrates resilience by enduring long hours. This standard implicitly values physical stamina as a key performance indicator. Corporate structures, from office layouts that require extensive walking to packed travel schedules for leadership tracks, are built upon this assumption of able-bodied consistency. These norms were not necessarily designed with malicious intent, but their exclusionary effect is profound.

Such outdated standards systematically penalize anyone whose body does not conform to this rigid ideal. For individuals with fluctuating health conditions, performance is often conflated with presence, and leadership potential is incorrectly tied to the ability to withstand physically demanding tasks. This creates a powerful incentive for employees to hide their needs, believing that appearing “easy” and non-disruptive is safer for their career than being transparent about their access requirements. The system inadvertently rewards concealment and punishes authenticity.

The Culture of Concealment and the Cost of Passing

The decision to hide a disability is rarely made lightly; it is typically driven by a rational fear of negative consequences. Employees worry about being judged, losing credibility, or being passed over for promotions if they are perceived as less capable or requiring “special treatment.” This fear is compounded by the risk of being seen as inconsistent or even untruthful if their need for support varies. To avoid this scrutiny, many will consciously leave mobility aids at home or push through pain during meetings, all in an effort to “pass” as able-bodied.

This pressure to conform often leads to internalized ableism, where individuals begin to absorb the societal belief that their needs are an inconvenience. They may hesitate to request simple accommodations, like a chair in a long meeting or a more ergonomic workstation, because they have been conditioned to minimize their footprint. The personal cost of this constant self-monitoring and suppression is immense, leading directly to burnout, worsened health symptoms, and increased absenteeism. For the organization, the price is just as high: the quiet loss of valuable talent who eventually leave for environments where they do not have to sacrifice their well-being for their career.

When Silence Becomes a Systemic Failure

Research reveals a troubling pattern: many organizations operate on a reactive accommodation model, addressing an employee’s needs only after they reach a breaking point. An employee who has hidden their condition for years may finally request support when their health is in crisis, but this request is often treated as a sudden and inconvenient problem. This reactive approach frames the need as an individual’s failure to cope rather than a predictable outcome of a rigid and unsustainable work environment. It creates a cycle where employees wait until they can no longer manage, and employers respond with ad-hoc solutions instead of systemic change.

This reactive trap is sustained by the dangerous conflation of physical presence with professional performance. Expert analyses consistently show that productivity and impact are not determined by the number of hours spent in an office or the ability to endure a grueling travel schedule. True value lies in the quality of work, innovation, and strategic contribution. When companies mistake physical endurance for professional merit, they not only exclude disabled talent but also promote an unhealthy and inefficient model of work for everyone.

Building a Sustainable Workforce with a Proactive Framework

Transitioning from a reactive to a proactive model of inclusion requires a fundamental shift in mindset and structure. The first step is to equip leadership with the knowledge to understand and support employees with fluctuating conditions. Managerial training should emphasize that a variable need for accommodations is a normal aspect of many disabilities and not an indicator of an employee’s commitment or credibility. This builds a culture of trust, empowering employees to be open about their needs without fear of reprisal.

This cultural shift must be supported by structural changes that redefine success. Organizations can decouple productivity from physicality by focusing on outcomes rather than hours worked or time spent in the office. Flexibility should become the default, not a special exception. This includes offering robust remote and hybrid work options, providing varied seating in all meetings, and designing adaptable schedules. When flexibility is standard practice, the burden is lifted from disabled employees to constantly disclose and justify their requirements.

Ultimately, a truly inclusive workforce is built on proactive design. Accessibility must be a primary consideration from the beginning, whether planning a new office layout, organizing a company retreat, or scheduling business travel. By anticipating a wide range of human needs, organizations can prevent exclusion before it occurs. This approach normalizes accessibility and creates an environment where every employee has the opportunity to contribute their best work.

The challenges faced by disabled workers in conventional settings revealed a deep-seated reliance on the myth of the “ideal worker.” The journey toward true inclusion required organizations to dismantle this outdated archetype and embrace human variability as a strength. By shifting from reactive fixes to proactive design, workplaces not only retained invaluable disabled talent but also fostered a more honest, resilient, and high-performing culture for all employees. This evolution demonstrated that when environments were built to support people as they are, everyone had a greater capacity to thrive.